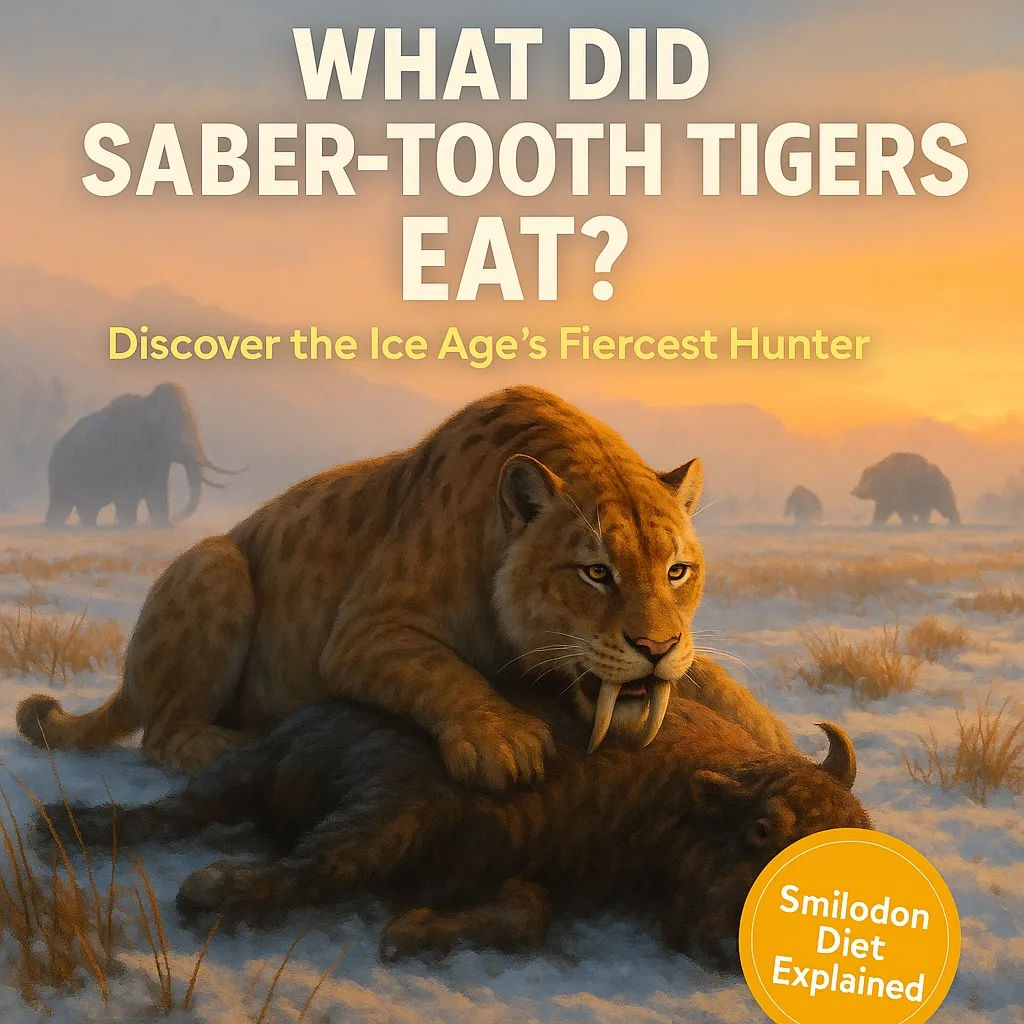

Discovering the Diet of Smilodon

Imagine a giant cat, heavier than today’s lions, creeping through Ice-Age forests, muscles coiled, its two enormous saber-shaped canine teeth gleaming. That’s Smilodon also known as the Saber Tooth Tiger. But what did Smilodon actually eat? Beyond the “big herbivore” cliché, modern research tells us much more: Smilodon wasn’t always picky, it adapted across regions and climates, and how it ate helps explain why it eventually vanished. Let’s dive into what recent science says about What did Saber Tooth Tigers Eat?.

Meet Smilodon

Before we explore its dinner plate, let’s meet the creature. Smilodon was a genus of extinct felids (cats) that lived in the Americas during the Late Pleistocene (about 2.5 million to roughly 10,000 years ago). Three main species are recognized:

- Smilodon gracilis — the smallest, older species.

- Smilodon fatalis — the well-known “classic” saber-tooth cat of North America.

- Smilodon populator — a massive version that lived in South America.

Smilodon is not closely related to modern tigers or lions, it belongs to a subfamily called Machairodontinae, while today’s big cats are in Felinae. So calling it a “tiger” is a fun shortcut, but not biologically precise.

Its body was powerfully built, extremely strong forelimbs, short but muscular legs, and those dramatic upper canines (which could reach more than 20 cm in some specimens). Fossils of Smilodon fatalis show a body mass of around 160-280 kg (350-600 lbs) depending on locality.

All these traits hint at how it lived, a predator built for power, not speed.

How Scientists Figure Out What Smilodon Ate

You might ask: how do we know what an animal that’s been extinct for thousands of years ate? Good question. Paleontologists use several clever methods:

1. Isotope and tooth-enamel analysis

By analysing carbon (δ¹³C) and nitrogen (δ¹⁵N) isotopes in fossil bones or tooth enamel, scientists can infer what kinds of prey an animal consumed (and by extension what those prey ate). For instance, if prey ate mostly C₃ plants (typical of forest vegetation) vs C₄ plants (grasses), their carbon isotope signature differs — and that passes up the food chain. One study on Smilodon fatalis canines found values indicating its prey mostly ate C₃ plants.

2. Dental microwear texture analysis (DMTA)

Tiny pits, scratches and wear patterns on teeth tell us how the animal chewed: flesh only, or flesh + bone, or tough hide and bone. A 2025 study found that populations of Smilodon (fatalis and gracilis) across different regions showed very similar microwear textures — suggesting they had a fairly generalist diet in terms of prey size, despite morphological differences.

3. Anatomical / biomechanical clues

The shape of bones, claws, limbs and the skull tell us what kind of hunting style the animal likely used. For example: powerful forelimbs + short legs = ambush predator rather than long-distance chaser. The long canines hint at a specific killing technique. A 2025 modelling study found that these sabre-teeth were “functionally optimal” for puncturing prey — supporting their use as specialised weapons.

4. Fossil context and associated fauna

If you know what other animals lived in the same place & time, you can infer what prey were available. For instance, at the fossil-rich Rancho La Brea Tar Pits (California), many Smilodon specimens were found alongside large herbivores like bison, camels and mammoth-relatives.

What did Saber Tooth Tigers Eat

Okay now for the fun part, the dinner menu of Smilodon. But instead of a fixed list, it’s better to think: “lots of large to medium-sized mammals, especially herbivores, depending on region & era.” Here’s a breakdown.

Likely Prey (based on current evidence)

| Prey type | Why plausible | Notes & caveats |

|---|---|---|

| Bison (e.g., Bison antiquus) | Many fossil associations, size fits predator | Strong evidence in North America. |

| Camels (e.g., Camelops) | Camel-like fossils in contaminated assemblages | Verified in North America. |

| Horses (genus Equus) | Large herbivore, present in Pleistocene faunas | “Hipparion” horses pre-dated Smilodon; so adjust accordingly. |

| Giant ground sloths (e.g., Megatherium type) | Big, slow-moving prey ideal for ambush predators | Evidence stronger in South America for S. populator. |

| Mammoth/mastodon juveniles (e.g., Mastodon) | Big but not fully grown = better prey | Juveniles more plausible than full grown mammoths. |

| Other large mammals (elk, llamas, peccaries etc) | Variety of fauna available; less direct evidence | Should be described as “possible” rather than certain. |

Key point:

Smilodon wasn’t limited to just one species of prey. The 2025 study shows that across space and time, Smilodon fatalis and Smilodon gracilis had very similar dietary habits, indicating they hunted a variety of medium and large prey rather than only mega-fauna.

Earlier ideas painted Smilodon as a specialist big game hunter (only mammoths or giant sloths). But the latest research suggests a more flexible approach, it adapted its diet depending on environment, climate and prey availability. For example, the Florida populations of S. fatalis and S. gracilis had indistinguishable microwear textures, implying similar diets despite being different sizes and in different contexts.

Hunting style & kill method

- Smilodon likely used its strong forelimbs to wrestle prey to the ground.

- Its long canines were not for slashing repeatedly through bone they were precision tools for delivering a killing bite (often to the throat or abdomen) when the prey was immobilised. This matches biomechanical modelling and wear analyses.

- The leg structure (relatively short legs) suggests ambush more than chase. Cover (trees, shrubs) would have helped. Some reconstructions suggest forest or bush habitats rather than open plains.

Scavenging?

There is some evidence Smilodon may have taken advantage of carcasses (by scavenging) when the opportunity arose but it was not primarily a scavenger. For example, studies of tooth wear show Smilodon did consume some bone (unlike species that strictly avoid bone) but did not have bone-crushing adaptations like hyenas.

Prey habitat & behavioural clues

- –Smilodon likely preferred habitats offering cover forests, bush, woodland edges which support ambush style rather than open sprint hunts.

- Some populations may have been social (or at least tolerant of one another) because many healed injuries in fossils (implying individuals survived long after being wounded suggesting help). However this is still debated.

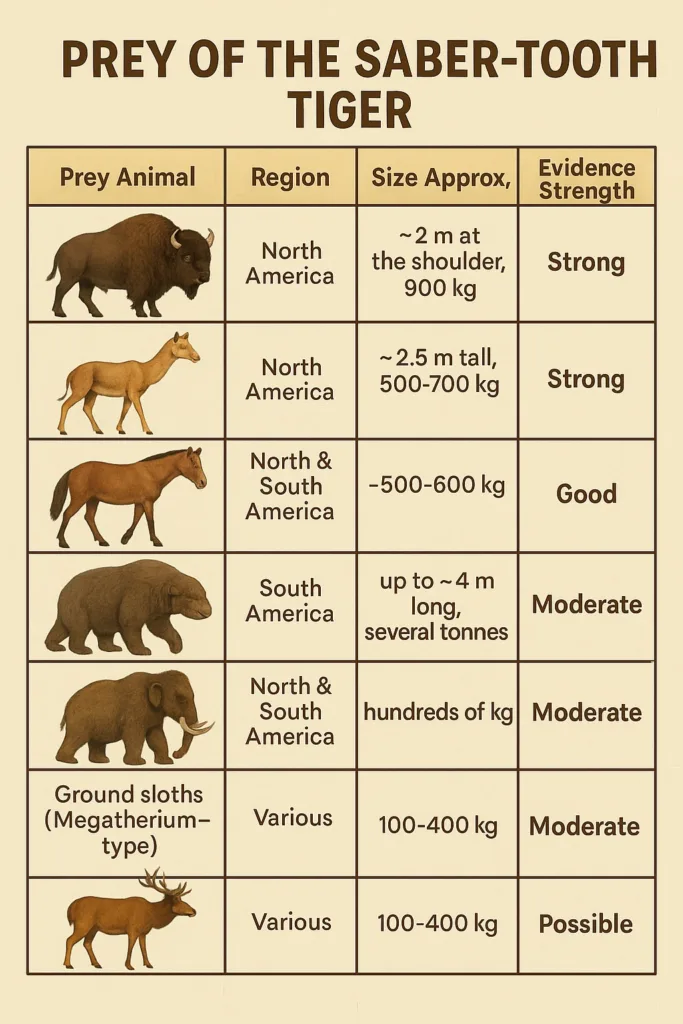

Table: The Ice-Age Menu of Smilodon

| Prey Animal | Region | Size Approx. | Evidence Strength |

|---|---|---|---|

| Bison (Bison antiquus) | North America | ~2 m at the shoulder, 900 kg | Strong |

| Camelops (camel) | North America | ~2.5 m tall, 500-700 kg | Strong |

| Equus (Pleistocene horse) | North & South America | ~500-600 kg | Good |

| Ground sloths (Megatherium-type) | South America | up to ~4 m long, several tonnes | Moderate |

| Mammoth/Mastodon juveniles | North & South America | hundreds of kg | Moderate |

| Medium herbivores (elk, llamas, peccaries) | Various | 100-400 kg | Possible |

Why Its Diet Matters — And What It Tells Us

What Smilodon ate connects to major questions: how it lived, why it went extinct, and what Ice-Age ecosystems were like.

1. Ecosystem role

As an apex predator, Smilodon helped shape the populations of large herbivores. Its presence tells us that prey species had to be abundant and suitably sized. If prey declines (due to climate or human impacts), predators struggle.

2. Extinction clues

Smilodon went extinct around the end of the Ice Age (~10,000-12,000 years ago) in many places. One hypothesis: because it relied on large prey, and those prey declined (due to climate change, human hunting, habitat shifts), the predator faced a food crisis. Research shows partial support for this but interestingly the 2025 study suggests Smilodon’s diet was quite adaptable, so extinction causes may have been more complex (not simply “no prey” but a combination of factors).

3. Comparative biology

Studying how extinct predators consumed prey — e.g., Smilodon helps us understand modern carnivores, their flexibility, and how ecosystems respond to change. Big cats today face prey declines, habitat change and human pressures so the fossil record offers a cautionary tale.

Fun Facts & Surprising Discoveries

Here are some cool details that kids (and adults) will love:

- Smilodon’s canines: A 2025 study shows those huge sabre-teeth were “functionally optimal” for puncturing prey, meaning they were extremely effective tools, but also likely made the cats more vulnerable when prey changed or disappeared.

- Fossils in Brazil: Smilodon populator, the largest species, is well-known in South America including finds in the Cuvieri Cave in Brazil.

- Surprising diet: A 2025 article (Science) reports that some saber-toothed cats (not necessarily Smilodon) may have hunted deer and forest creatures more frequently than previously thought, showing the “grassland big game” stereotype is incomplete.

- Wounds and survival: Lots of Smilodon fossils show healed injuries (broken bones, healed canines), suggesting individuals survived after serious trauma hinting at possible group behaviour or long lifespan despite risks.

“Did You Know?” Sidebar (for kids)

- “Did You Know: Smilodon’s sabre-teeth could reach 28 cm in S. populator! That’s about the length of a ruler…”

- “Smilodon lived alongside enormous herbivores like bison and camels imagine a giant cat chasing a giant bison!”

- “Despite being so bulky, Smilodon likely ambushed prey rather than ran them down it relied on surprise and strength.”

- “One study found that Smilodon fatalis individuals in Florida and California had almost identical diets, even though they lived in different environments.”

Frequently Asked Questions

What did saber-tooth tigers eat?

They ate large herbivores like bison, camels, horses, ground sloths, and possibly mammoths — basically big animals they could ambush and overpower.

How did they kill their prey?

They used strong forelimbs to wrestle prey down, then used their long canines to deliver a killing bite — often to the throat or belly rather than slashing wildly.

Did they eat humans?

There is no reliable evidence that Smilodon regularly hunted humans. Most human-sabertooth interactions remain speculative.

Why did they go extinct?

They likely faced a mix of challenges: decline of large prey, climate change at the end of the Ice Age, habitat shifts, and possibly human competition. Their specialised lifestyle may have made them less adaptable. The long-toothed “weapon” that once gave them advantage may have become a liability.

Were they scavengers?

Occasionally, yes. But Smilodon was primarily a hunter, not a bone-crushing scavenger.

Summary

The “saber-tooth tiger” (Smilodon) wasn’t a one-note predator. It was a powerful ambush cat that hunted a variety of large mammals across the Americas. Thanks to modern methods (isotopes, microwear, biomechanics) we know its diet was more adaptable than once thought. It relied on big prey, but was not locked in to only one species or habitat. That flexibility helped—but perhaps not enough—when the Ice Age ended, habitats changed and prey began to disappear. Teaching kids about its diet gives them a window not just into one beast, but into whole ecosystems at a changing edge of time.